Spotlight on Five Feminist-Minded Short Stories with Elements of Horror

Joyce Carol Oates once so perfectly wrote, “One criterion for horror fiction is that we are compelled to read it swiftly, with a rising sense of dread, and so total a suspension of ordinary skepticism, we inhabit the material without question and virtually as its protagonist: we can see no way out except to go forward.” It is this very reason that I so love the horror genre; it transports its reader to another world where one can observe, and be an entirely new entity, whether person, monster, witch, or troll. When you combine horror with the feminist short story, you enter a whole new realm that’s even more terrifying than any Pinhead from Hellraiser or Damien from the Omen. The horror delves into reality, where much can be hidden beneath the façade of such vanities as a life of wealth, the perfect marriage, or an idyllic community.

The tales below are a sampling of five feminist short stories that do indeed leave us with a “rising sense of dread” because sometimes, the horror is too personal.

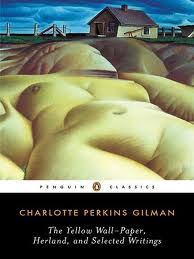

The Giant Wistaria

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

It’s shocking once you’ve finished The Giant Wistaria to realize that it was published in 1891, when it seems as if it were written not so long ago. The story takes place during two time periods, the 1700s and the 1800s. The former century begins with an English family and we’re dropped into the middle of the most scandalous of family dramas–their daughter has just given birth out of wedlock, and the parents are fleeing to England to escape any disgrace to their family name.

Fast toward to the late 1800s; the house from whence they fled is now decrepit and has been virtually swallowed by a gigantic Wistaria vine. A wealthy young couple and their friends happen by, completely enchanted by what they interpret as rustic charm, they assume that it must be haunted and rent it immediately. As the three couples drink, eat and laugh, they describe the prospect of an eventful summer chock-full of ghosts that hopefully inhabit the house. After the first evening, their fantasies come to fruition as half of the group awakens to find that they’ve had the same dream of a young woman with a mysterious bundle in her arms and a red cross around her neck. They soon find that their collective dreams were more than a mere case of indigestion (to quote A Christmas Carol).

The Giant Wistaria is chilling for several reasons. First off, the punch that is delivered is done so in only a few pages; not only is CPG a feminist, but she’s also a powerful storyteller and is able to intertwine the two seamlessly. Another sobering facet of the story is the juxtaposition of the two time periods, the people who exist in each one, and finally, the full-circle of tragic events. CPG was a master of collective human emotions and is able to make you feel guilty and sickened by indirectly referencing class and gender inequality.

A Good Man is Hard to Find

Flannery O’Connor

I knew very little about Flannery O’Connor when this collection of short stories was recommended to me. I knew that O’Connor was Irish Catholic, and that the stories were written in the mid-20th century. Needless to say, as I finished the first story, which is also the namesake for my particular edition, I was completely taken aback. “The person who suggested that I read this should have warned me!” I thought. Like so many of the other stories in this article, it’s thrilling to read a gem so subversive that it still shocks nearly 70 years later.

I knew very little about Flannery O’Connor when this collection of short stories was recommended to me. I knew that O’Connor was Irish Catholic, and that the stories were written in the mid-20th century. Needless to say, as I finished the first story, which is also the namesake for my particular edition, I was completely taken aback. “The person who suggested that I read this should have warned me!” I thought. Like so many of the other stories in this article, it’s thrilling to read a gem so subversive that it still shocks nearly 70 years later.

As the story begins, we meet a family comprised of three young children, their mother and father, and the paternal grandmother. Like many of O’Connor’s other writings, A Good Man is Hard to Find is set in the South, and as the family embarks on a road trip to Florida we learn that a murderer is on the loose by the nickname, “The Misfit.” From start to finish, the grandmother is a pill. She believes the past was best, children should be quiet, women should always be ladies, and her opinion is always right. Basically, she’s the southern queen of unsolicited advice. O’Connor is a master at tapping in on a personality type that annoys most people because they are in everyone’s lives in some form. Because of that, we as readers are extended participants in this very long road trip. In addition to being an expert character study, O’Connor takes us on a trip through 1940s/50s Georgia in the summer. It’s hot and dusty with a killer on the loose. They are alone on the road in a deserted part of the state where gas stations come only intermittently, setting a tone that leaves us unsure of our surroundings and insecure about the future. As the trip goes on, the grandmother sends the family on a wild goose chase, seeking out physical proof of a misplaced memory. This dirt detour sends the family into a downward spiral that puts them face to face with what the grandmother hoped to avoid from the outset–the Misfit.

At first read, A Good Man… could seem like nothing more than a story about an incredibly annoying grandmother and a gang of psychos. However, this is one of those great stories that unfolds a multitude of onion-like layers that encompasses race, religion, class and poverty, region, crime, place in history, Civil Rights, and gender roles, amongst others. However you choose to read this story, as one of good old-fashioned murder, or a story of murder inextricably bound with issues of class, race and religion, you are left with comparable sense of dread, and maybe just a hint of schadenfreude as the grandmother finally gets her lips zipped.

The Joy of Funerals

Alix Strauss

The Joy of Funerals differs from the other titles in this round-up because it is a collection of short stories that end up connecting in the end, which also packs a great ah-ha as the tales come into the final braid. Similar to Strauss’ most current book, Based Upon Availability, each story is unique in its own right, and the culmination of all the interlaced stories is an extra cherry on top.

Each story is about how women, whether individually or in a group, deal with the grief they experience over the loss of a loved one in New York. Strauss plunks us down smack dab into their lives by crafting mournful imagery and offering variety of well fleshed out characters. Each character, in only a few pages, is described in such thorough detail that you feel like you not only really know them, but can completely empathize with what they are experiencing through their grief. In one story, a woman burns a photograph of her husband and eats it on her breakfast cereal, and while reading it, you are eating the ashes with her–you can smell it, taste it and feel the loss as if you’ve been punched in the belly. In another story, a woman’s behavior is so deceitful that it leaves the reader with a personal sense of betrayal, but also left me to unfortunately identify with the character’s insecurities. To me, only a true master of art can make you identify with the flawed characters, al la the films Spring Breakers and Happiness. Full disclosure, I found myself crying throughout the majority of the book because the stories are crafted in such a way that they strike the core of shared human experience with concern to love and loss.

We So Seldom Look on Love

We So Seldom Look on Love

Barbara Gowdy

The short story collection, We So Seldom Look on Love is truly a forgotten treasure. Reading it nearly seventeen years ago, it has remained implanted in my mind, and the physical book has stayed with me through every move of my life because of it. The short story that I’d like to hopefully introduce you to, which is also the title for the book, is the reason why banned and challenged books are so important for the youth. Decades ago, this creepy, gross and arguably offensive story exhilarated this gal as a fifteen-year-old and helped to make her the liberal bitch that she is today.

The story is told from the point-of-view of the main character as she reflects on her childhood as a blossoming necrophiliac and fast forwards to current day when she is publicly disgraced as her sexual proclivity becomes mainstream knowledge. As a child, she realizes that her infatuation with dead animal corpses: the smell, the blood, their energy, et al, will prevent her from attracting and sustaining any form of friendship. As she gets older, she accepts her sexual attraction to male corpses, admitting that she is unable to fall in love with any living man, and that plenty of corpses have broken her heart. Naturally, she enters medical school as a means of gaining access to these potential and cadaverous love interests. Though the idea of engaging in oral sex with dead tissue may seem unattractive to most of us, I give kudos to Gowdy for her character’s unflinching acceptance of her sexuality at so young of an age. Teenage girls, and really, most women, have mixed emotions regarding their sexual bodies, and it’s refreshing to read about a young woman who doesn’t deny herself those inclinations.

The White Cat

Joyce Carol Oates

The White Cat is one of those great stories where the plot may not be as it seems, and its interpretation can be fluid depending on its reader. Ostensibly, we’re reading a tale about a WASP of a man, his younger wife, and their evil Persian cat, Miranda. As we delve deeper into the mind of Julius Muir and his family life, the storyline thickens as we are fed bits of information that make Julius’ home life seem less than perfect, though he would have you think no other way.

It can be argued that the story is a portrait of the building and collapse, aka psychological break-down of the main character, Julius, and since much of it is from his point of view, it’s not exactly clear where the truth lies. We are to believe that Miranda the cat is evil because of said evidence: “…as the cat grew older and more spoiled…it became evident that she did not…chose him.” His subsequent reaction contains a crumb of hilarity as he reconciles that he will handle this situation by killing the cat because her ambivalence of him is an affront to this man who “knows who he is.” Because Mr. Muir purchased the cat for his wife, he believes himself to be her sole master and therefore has the right to end her life since he brought her into being (at least into this own house).

As we read on, the facts become murky. We wonder, what has happened for the past ten years? There is no indication that their contemptuous relationship has built over the decade of co-habitation, and seems to be a relatively recent occurrence. An occurrence that has also surfaced with the advent of his wife making more decisions independent of Julius, perhaps. Is the quirky Persian evil, living to cause Mr. Muir a life of anguish? Is he simply ignoring characteristics are inherent in the sometimes fickle feline species? Or, is he attributing his wife’s human characteristics to his cat instead of facing up to his own troubled family life; a life that is seemingly so perfect in every way?

Part 2 can be viewed here.